Part One: Origins

[Nb. the following bio is based on shared experience and interviews with my brother. All quotes are his unless otherwise noted.]

Trenton, New Jersey’s reputation as a failed city is sadly well-deserved and I’m being kind, because I was born there. The state capital and former home of thriving steel and ceramics industries in addition to Westinghouse and General Motors factories, Trenton possesses an outstanding history (by American standards). Founded in 1679 by Quakers fleeing religious persecution in England, it was the site of George Washington’s decisive victory in the American Revolutionary War when, on Christmas Day 1776, his army crossed a frigid Delaware River to stage a surprise attack on the Hessian troops garrisoned there.

For a while after the war, there was talk of Trenton becoming the capital of the newly independent confederation but Washington D.C. was chosen instead.

But by the late 1800s and well into the twentieth century Trenton was an industrial center manned by the thousands of European immigrants, including our grandparents, who flocked there for the jobs it provided.

Promotional poster, 1915

In the 1950s, when the factories closed, Trenton was forgotten by local administrators, not to mention the world, and for at least half a century has qualified as a post-industrial ruin.

Portion of the Roebling Steel Factory

Neglected by its administrators, abandoned by industry, poverty levels rose and racism became more pronounced; Martin Luther King’s assassination (April 4, 1968) brought African-Americans to the streets in a furious spate of riots that resulted in bloodshed, destruction and an abiding rancor from which Trenton has arguably yet to recover. But before that, while on the decline in the 1950s and 1960s, it wasn’t the worst place to grow up.

Our family: David, Helen and Frank Jr. (standing) and Frank Sr. on the chaise lounge with young Christopher and myself, c.1962

Candidate for America’s best pizza, on Hudson Street

We lived on Centre Street in a fine house with a lovely yard and a magnolia-shaded patio near an old Baptist church with a columned entrance, and not quite far enough from the state prison, a formidable brown brick fortress occupying a city block that lent the surrounding neighborhoods a sense of doom. But we had decent schools, a great park, music stores, some of the world’s best pizza (locally known as ‘tomato pie’), a couple of grand movie theaters and two very respectable jazz clubs.

Frank decided to become a musician in 1959, following his “first and only epiphany” which happened on a summer’s day with our mother, Helen.

Helen J. Rafalowski-Golia, 1950s

It was at a church-sponsored picnic at Kuser Farm Park in Hamilton Township where our uncle, Zigismund Rafalowski, was playing accordion with a local band. There was a band shell surrounded by trees, an Arcadian setting, said Frank:

…like a forest filled with people dancing, laughing and listening to the music. It was the first time I saw live music performed that I can remember. I was eleven and a feeling took me over; it was a spiritual experience.

In addition to our uncle, the band featured a saxophonist (Hap Walter) and a bassist, but Frank was especially struck by the drummer, whose name coincidentally was Hy Frank. “His drums were pearl gray, and when he let me sit behind them, I was mesmerized. I was an altar boy and thinking about the priesthood or becoming a lawyer.” But when Hy Frank gifted him a set of drumsticks “that all disappeared.”

Frank’s first drumsticks had belonged to Don Lamond, formerly with Woody Herman’s big band

Frank spent the next two years “pounding on the couch” until he could earn the money (and convince our father to grant permission) for lessons. It’s not that Francis J. Golia Sr. did not love music, on the contrary, our house was equipped with an excellent ‘hi-fi’, a combination radio and record player, and one of Frank Sr.’s fondest dreams was to run a jazz club in New York.

Helen and Frank in the front of a Lincoln Zephyr, c. 1942 with newlywed friends in the back.

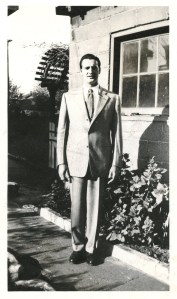

Francis J. Golia Sr., 1946

Our father was a first-generation Italian immigrant, a construction worker who graduated high school and wanted his sons to attend college and find jobs less backbreaking than his own. His attitude resembled that of many of his peers, that children should have music lessons to refine their characters and show their parents’ care for their education, and that while teaching music was an acceptable, if modest profession, performing it most definitely was not.

But Frank was persistent, our mother interceded and Hy Frank was engaged as his drum teacher. Hy picked Frank up in the afternoons at Holy Cross Grammar School (on the corner of Adeline and Arch Street) “in a Ford Fairlane with the ashtray full of cigar butts” and sometimes borrowed money from his student but always paid him back.

Hy was the perfect first teacher, accomplished and patient with an impressive New York air about him, in his fedora and a somewhat crumpled suit; he had a sharp wit and a halo of frizzy hair like one of Three Stooges. Although he was a quick study, it took Frank time to afford a drum set. He meanwhile made a practice pad out of a block of wood and a linoleum tile, much to the relief of our couch.

Hy was the perfect first teacher, accomplished and patient with an impressive New York air about him, in his fedora and a somewhat crumpled suit; he had a sharp wit and a halo of frizzy hair like one of Three Stooges. Although he was a quick study, it took Frank time to afford a drum set. He meanwhile made a practice pad out of a block of wood and a linoleum tile, much to the relief of our couch.

Like many musicians of his day, Frank’s first experience practicing and performing with other musicians came in a high school band. He was the only junior in the Pep Rally Band at Trenton Catholic High School; the drummer had fortuitously graduated. Pat Di Giuseppe was bandleader and they rehearsed in his garage. Mike Allen played piano; Bill Lowe, (“who lived on Ferry Street and later became an engineer”) played trombone; there was a saxophonist, clarinetist, and later a trumpet player plus a bassist “who was a guitar player who played the G-string for a low/bass sound.”

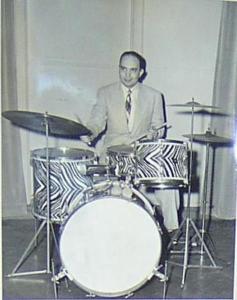

In 1963, Frank began a two year stint of study with jazz drummer

Tony DeNicola, c. 1960

Tony DeNicola (1927-2006) who gave lessons on the third floor of Lombardo’s Music Store (Hamilton Ave.) about a half-mile from our home. DeNicola had a reputation and as a teacher represented a step up. He’d studied with the renowned drummer/educator Henry Adler (1915-2008) in New York, whose place was “a hangout for the world’s top drummers” and regularly played with bands in New York. DeNicola had shared a stage with Harry James, Charley Ventura “and a slew of musicians who came to Henderson’s,” a Trenton club that along with Club 55 (also downtown) booked jazz greats like Coleman Hawkins, Clark Terry, Kay Winding, Doc Severenson, Phil Woods and Cat Anderson (who played with Duke Ellington).

As a teacher, DeNicola was “more articulate and had more background [than Hy]”. He was impressed with Frank’s talent and said he’d be “one of the best.” Frank took two half-hour lessons back to back at six dollars an hour, money he earned cleaning a private girls’ school called Miss Ireland’s (“my janitor business”), running a paper route, mowing lawns and doing house and yard chores for one of our father’s older sisters. After three and a half years he’d saved enough for the drum set – 650.$ – and he purchased it from the Universal Drum Studio on South Broad Street, in February 1963.

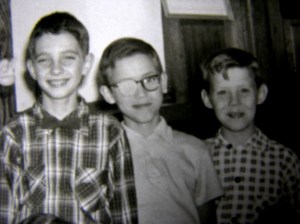

Frank (center) wore glasses from an early age owing to a severe astigmatism. Pictured with classmates at Holy Cross School c.1955

Around that time while playing with the Mercer County Youth Band in Cadwalder Park, Frank met pianist Kirk Nurock (1948 – ) who became his first musician friend and collaborator in the real world. Nurock was a prodigy, Frank said, and the band (with Russ Spirella/bass and Joe DiVito/vocals) played house parties, bar miztvahs, dances and jazz gigs, rehearsing and performing original tunes and standards. At sixteen, Frank could call himself a “semi-professional.”

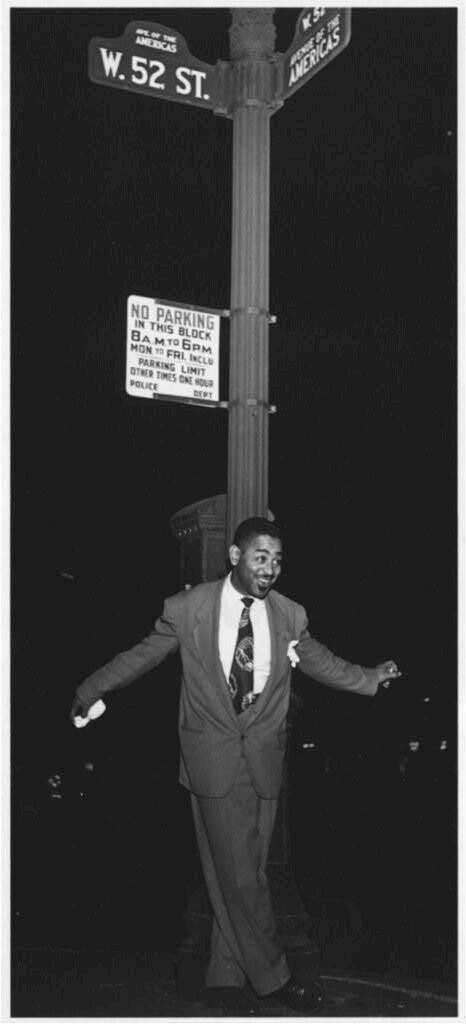

He had some exciting times with Kirk whose father, a Princeton ophthalmologist, believed in music and helped promote the career of Johnny Richards, an arranger with Stan Kenton. Nurock threw a cocktail party for Richards and Frank played there with Kirk. It was a posh gathering, but even better was the trip to New York to watch Richard’s band rehearse at Birdland, the storied club on 52nd Street, on a day when bebop pioneer Dizzy Gillespie turned up to say hello. “All the trumpet players [in Richard’s band] paid homage” said Frank, who had long admired Dizzy’s genius.

Dizzy, c.1948. Photo: William Gottleib, Library of Congress

In the winter of 1964, Frank played with Nurock at a place called the Cellar (“a delicatessen and a finished off basement”) in the Bristol (N.J.) Shopping Center whose owner was trying to draw business and had contacted Nurock’s father to see if Kirk could play Aside from Kirk and Frank, band members included Frank Zuback/ bass; John Mack/trumpet, conductor of the Pennsbury High School Jazz Concert Band; and Chuck Wicker/tenor, formerly with Woody Herman who later became a professional copyist for musician/arranger Don Sebesky and others.

After high school, Kirk went to Julliard and he and Frank lost touch. Frank had graduated first and immediately found a job at Trenton’s Motor Vehicle office as part of a plan to save money to go to Berklee College of Music in Boston. But when our mother was diagnosed with cancer, Frank and our brother David, several years his junior, worked to help support the cost of her treatment which took place in Philadelphia. Our father began meanwhile showing signs of a heart condition that would eventually prove fatal. Fortunately, “there was money in live music” and thanks to his weekend gigs Frank was soon in demand enough to quit his day job and play full time.

In May, 1966, fellow Trentonian and alto saxophonist Richie Cole (1948 – )who was studying with bandleader/composer/alto saxophonist Phil Woods (1931-2015), asked Frank to play on his demo. The session took place in New Hope, Pennsylvania, at the former home of the late Charlie Parker where Chan, Parker’s common law wife, now married to Woods, still lived. The tape of that session, with Phil Woods playing piano, is still out there, somewhere… In the winter of 1966 to early-1967, Jack Wygand, an organist from Lawrenceville, New Jersey, hired Frank to accompany his band in Philly. While with Weigand, Jilly Rizzo, a friend of Frank Sinatra who owned the popular Jilly’s Saloon in New York, hired Weigand to be the opening act at his other club in Miami, right next to Dean Martin’s .

Weigand’s band played the first set at 10:30, followed by another warm-up band and the main act, all of which appeared in the club’s main hall. Frank occasionally sat in with the name bands, including as part of a trio with Jamaican-American pianist Monty Alexander (1944 – ) and bassist Paul Chambers (1935-1969) who managed to record a dozen albums in his brief life, including with Miles Davis. Popular performers like singer Connie Francis and the Supremes came to Jilly’s; it was “ a very flashy crowd” said Frank, who enjoyed a little flash himself. By this time, with steady paychecks he was able to afford the kinds of cloths suited to his profession: a tuxedo and suits in different colors and some good (i.e. Italian) shoes.

My brother, who never drank much, described Weigand, who was around 42 at the time, as “an astute alcoholic.” Frank hung out with saxophonist Alessio ‘Sonny’ Trianfetti, who was just a few years older and whose family had a restaurant in Chambersburg, Trenton’s Italian neighborhood, ran a vending machine business, lived in a large house by the Delaware on the prestigious River Road and was said to be ‘connected’ i.e. in with the mob. ”Sonny,” Frank recalled, “had an imported blonde and a suitcase full of pep pills” and together they cruised Miami in Sonny’s rented car to hear the bands in what was then a “hoppin’ town.” They had mustaches and were frequently mistaken for Cubans, which gave Sonny, who spoke “two words of Spanish” quite a kick.

After Miami (Spring, 1967) Frank found work in Brown’s Hotel in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York, the bucolic inspiration for the Hudson School of painting.

Photo: Corneel Verlan

Set against a mazelike backdrop of rolling hills and lakes, Brown’s was the jewel in the crown of the so-called Borscht Belt, a series of luxurious hotels catering to upper middle class Jewish families from the New York area.

Brown’s Hotel, Catskills

In the 1940s, Brown’s was a mafia playground and for some, a last resort, as more than one body was disposed of in Lock Sheldrake, a couple of miles from the hotel. But by the 1960s when Frank worked there, it was a family place ensconced in greenery, the perfect country escape for city folk. It’s motto, “there’s more of everything,” captured the optimism of the times and the wish of every aspiring American.

Lighthearted entertainment was called for and the hotel’s Derby Club hosted floor shows with comedians like Jerry Lewis, Dick Shawn, Bob Hope, George Burns, and Woody Allen, and performers like Israeli vocalist Alisha Kashi, Sammy Davis, Tony Bennett and Harry Belafonte.

Catskills crowd, c.1960s

The Pocono Mountains (northeast Pennsylvania) also had resorts that offered live music attractions; Frank played at Strickland’s Mountain Inn, a place popular among newlyweds. In the summer of 1967, he met a painter named Lois Obshatkan, a sylph-like blonde he would always recall as the love of his life. It would have been a wonderful time, were it not for the fact that our mother was dying. Everywhere he played, Frank sought out the quietest place with a payphone where at night, before work, he’d call home.

Frank had just turned 22 when our mother’s condition worsened and Lois accompanied him to the hospital in Philadelphia. On August 25, 1967 , Helen Joanna Rafalowski Golia (b. February 20, 1923) left this life while her sons Frank and David and her husband held her hands. It’s not that Frank’s life changed substantively after that; he continued playing and studying. The autumn of 1967 found him living in Atlantic City, close to jobs at the Jockey Club (where he played with alto saxophonist Gene Quill) and local casinos. But anyone who has watched a loved one suffer and be inexorably drawn away, knows that it changes you on some ineffable level. Frank was no longer young, he was a man now, grief-stricken and driven. He and Lois parted paths and around the same time, he started writing music.

Francis J. Golia, c. early 1970s. Photo: David. J. Golia

(Continued, in ‘Bio, Pt.2’ from the main menu)